The history of apartheid in South Africa is littered with many injustices, pains, and struggles. Amidst that, our glorious country, Jamaica, shines once again through the work of one of its sons, Mr. Michael Archer. Archer helped to redefine the South African urban landscape as part of the reintegration efforts of the African National Congress during the post-apartheid era.

Born in May 1953, Archer, his brother, and two sisters grew up in Vineyard Town, Kingston, Jamaica, with their father, a real estate agent, and their mom, a pharmacist.

THE MAKING OF A DEVELOPMENT ENGINEER

With a civil engineering degree obtained from the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine campus, Archer headed to the Ministry of Works in the 1970s. His appointment as resident engineer in 1977 led him to work on the first phase of the Mandeville bypass in Manchester. Archer moved on to the then Ministry of Housing (MOH) in 1978, where he was involved in activities at the Sites and Services (S/S) Unit that largely aided in rounding out his technical expertise as a development engineer. The S/S Unit was incorporated as a public company, called EDCO (the Estate Development Company), in 1981. After two years, Archer became general manager with oversight for several government initiatives, including school building projects, infrastructure works for the Ministry of Agriculture, and the construction of HEART academies under the Office of the Prime Minister. He also managed the development of the Catherine Hall community in Montego Bay, Nannyville and Seaview Gardens in Kingston, and De La Vega City in Spanish Town.

In 1978, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) stepped in to assist the government with funding for the Housing Guarantee Programme. Managed by EDCO, it was this project that firmly established a relationship between USAID and Archer, which eventually led him to South Africa.

After 12 years in the public sector, Archer said that he exited and began working as a private consultant, joining Minister O.D. Ramtallie at the Ministry of Construction and Housing in 1989 in this capacity. He assisted with the roll-out of Jamaica’s first public-private partnership project for the development of 10,000 low-income housing units in Greater Portmore, St. Catherine. His position as the government’s engineering consultant was upgraded to that of project manager.

MANDELA RELEASED! TIME TO RE-DEVELOP

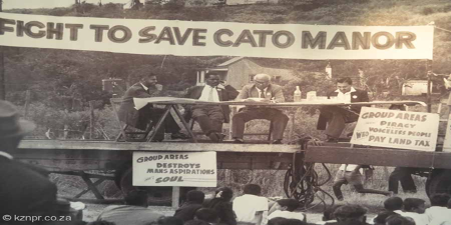

When the news broke that Nelson Mandela was going to be released on February 11, 1990 from his 27-year imprisonment in South Africa and that the oppressive South Africa Group Areas Act (GAA), passed in 1950, was to be repealed, USAID saw an opportunity to do development work in that country.

The GAA ensured racial separation between blacks and whites, eliminated mixed neighborhoods in favour of racially segregated ones, and allowed for separate development paths for the various South African racial groupings. It also allowed the government to confiscate and clear properties designated for particular racial groups.

USAID asked Archer for his resume, which he submitted, but gave it no serious thought until towards the end of 1992, when USAID again raised the offer. Archer said,

“When I refused, USAID approached me with a contract to sign, divulging that they had been having a series of urban development discussions for South Africa with the African National Conference (ANC), and the latter was very concerned that there was no black representative on the team.”

Having seen his work in urban renewal in Jamaica, USAID was convinced that Archer was aptly suited for the job and had told the ANC about him.

Archer said that he had initially rejected the offer because he feared moving his young family to South Africa, given the level of violence that had been reported during the liberation struggle. However, when he heard that the ANC was requesting that he come to ensure black representation on the project team, he “had to acquiesce.”

CATO MANOR

Under the previous apartheid regime, with the GAA in force, blacks were not permitted to enter white-designated areas. Their movement was only allowed under strict circumstances and required a pass issued by the authorities that gave access to restricted areas for a specified time and purpose. However, this was about to change. With the GAA repealed, blacks could now live in urban centres previously designated for white people, such as Durban.

Cato Manor was in Durban, and the fighting by its Indian owners had been fierce as the government tried to clear out the neighbourhood in the 1950s.

Due to the dispute and controversy over the land, Cato Manor remained undeveloped and had now become the focal point for urban renewal efforts.

Inspired by Archer’s performance on the Greater Portmore initiative, USAID saw Cato Manor as the perfect place to begin its efforts to build 40,000 housing units that catered to different income groups in the society, with Archer as the lead engineer.

Archer landed in Durban in January 1993, and his pregnant wife, Debra Anne, and their two young daughters joined him in July. By September, their first son, Mikhail, was born.

REMODELLING THE HOSTELS IN DURBAN

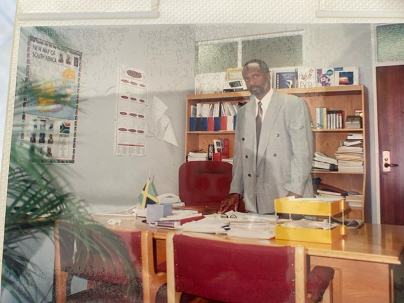

After three years working on USAID’s US$200 million project in South Africa as a consultant, Archer was offered the position of Chief of Party (Project Head). His portfolio included major development works in Durban, Johannesburg, Cape Town, and East London, all major urban centres at the time.

Archer also shared about another seminal project that he managed: the remodeling of hostels in Durban. These units once housed blacks who had worked as part of the South African industrial complex, but were now going to constitute the newly-liberated local labour force.

Be it known that although racist policies impeded South African blacks, the country’s industrial base was still being serviced by them. For example, the country hosted a manufacturing plant for German luxury car maker BMW for its right-hand drive vehicles. It also had nuclear energy resources that made it one of the world’s most efficient producers of electricity at the time, a fact that stood in stark contrast to some of the black townships that had yet to access electric power.

To maintain the country’s industrial prowess, space was needed to accommodate the workers who supported it; hence, the hostels. Crafted in the spirit of the apartheid era, these structures had been constructed to remove the dignity of their inhabitants, who had to share the facilities with very little room for individual privacy.

The task was now to restore dignity, in tandem with the incarnation of the renewed South Africa—a feat to be accomplished by transforming the hostels into 128,000 self-contained studio/apartment units, each with its own amenities.

Archer reported that the remodeling work required creative financing, which the ANC raised by selling a stock of petroleum products that had been stored as part of the country’s energy security policy, while international sanctions were levied against the government.

Archer was also able to oversee the social engineering of the new society while the redevelopment projects were being conducted. Masons, carpenters, plumbers, et cetera, benefited from on-the-job training—a strategy that improved the existing labour force and added to its ranks. This was sure to assist in the overall development of South African society, especially amongst the formerly oppressed blacks.

ARCHER’S FIRST-BORN SON WAS A FIRST FOR JAMAICA AND SOUTH AFRICA

In September 1997, Archer’s contract ended. He decided to return home, a move he considered with a sense of deep appreciation as he saw how much the journey had impacted him. Moreover, he saw how he had impacted the country—an accomplishment that had him receiving a formal letter of commendation in 1995 from the U.S. State Department in recognition of the work done in South Africa.

Not only had Archer been involved in re-designing the urban landscape of the new South Africa, but he had also helped to restore life and dignity to a people who had become the beneficiaries of racial oppression.

Furthermore, while in South Africa, his first son, Mikhail John, had the distinction of being the first black child to be born in one of the country’s major “white” hospitals—Kingsmeade.

So, in more ways than one, Michael Archer, a Catholic, has embodied the words penned by our forefathers, who decreed that Jamaica would be a nation that would play her “part in advancing the welfare of the whole human race.”

As the walls of apartheid came crumbling down in South Africa and a new nation emerged, it was re-built with contributions from our native son through hard work, vision, and knowledge gleaned from the place we call home—Jamaica, land we love.

______________________________________________

Contact Gordon M. Swaby (Engineer by profession and a Kingdom Visionary) at freedomcomerain@gmail.com.

“Jamaica Rising” looks back on Jamaica’s contributions to humanity against the backdrop of our prophetic destiny laid out for us through God’s Word and our Motto, Anthem, and Pledge (hereafter, referred to collectively as the MAP). It is hoped that by doing this, we will become midwives of destiny, helping to propagate God’s will for this nation, its inhabitants, and the wider humanity.

Do you know a story of a Jamaican pioneer? Email us at freedomcomerain@gmail.com.